Current Status

Not Enrolled

Enroll in this course to get access

Price

Closed

Get Started

This course is currently closed

Course Content

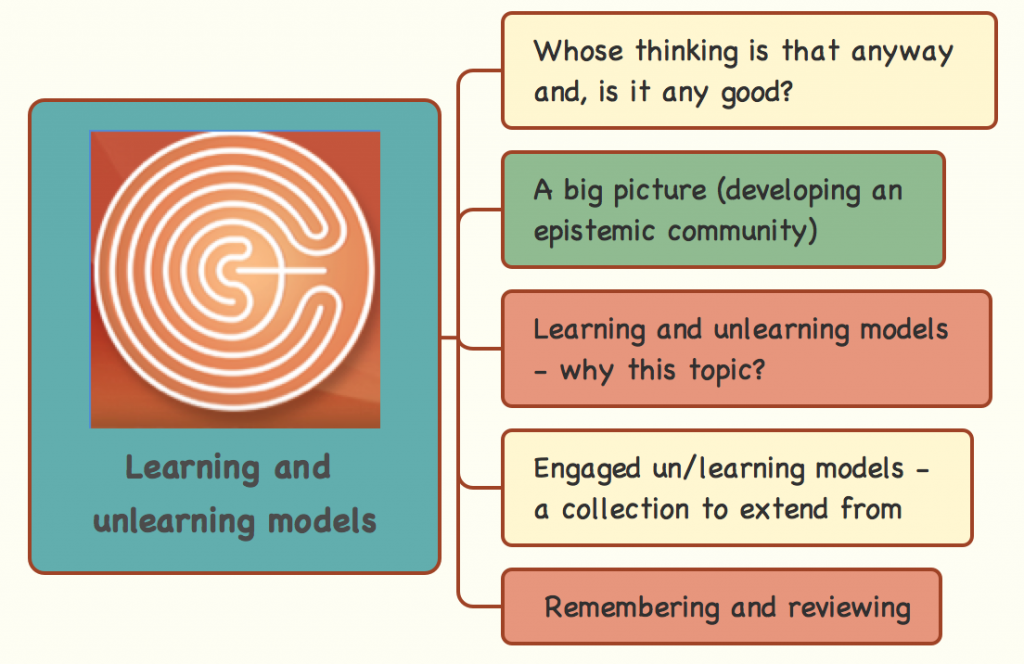

Whose thinking is that and, is it any good?

5 Topics

You don't currently have access to this content

Lesson Content

0% Complete

0/5 Steps

The big picture – an epistemic community capable of critique

6 Topics

You don't currently have access to this content

Lesson Content

0% Complete

0/6 Steps

Learning/Unlearning models – why this meta-topic?

3 Topics

You don't currently have access to this content

Lesson Content

0% Complete

0/3 Steps

Engaged un/learning models – a collection to extend from

10 Topics

You don't currently have access to this content

Lesson Content

0% Complete

0/10 Steps

Scholar skills 4 – Remembering & reviewing

5 Topics

You don't currently have access to this content

Lesson Content

0% Complete

0/5 Steps

Activities – Learning and Unlearning

4 Topics

You don't currently have access to this content